ETHNIC BULGARIANS IN MALA PRESPA AND GOLO BRDO

Tanya Mangalakova

Tanya Mangalakova

from: IMIR- www.imir-bg.org

Lake Prespa is situated in the territories of Albania, Greece, and Macedonia. At present, there are 9 villages in the Mala Prespa area inhabited by 5-7 thousand people some of whom have Bulgarian, and some – Macedonian consciousness. Ethnographer Vassil Kanchov cites Pouqueville mentioning that “in the early 19th century, Prespa was populated with Bulgarians alone. Arnaut migrations to Prespa began from the village of Trn or Tern, lying between theDevol River bed and Lake Mala Prespa, and then moved up further to the north”1. These villages are Eastern Orthodox and have both Bulgarian and Albanian names – Gorna Gorica (Gorica Madh), Dolna Gorica (Gorica Vogel), Tuminec (Kalamas), Glubočani (Golumboc), Šulin (Belas), Pustec (Likenas), Tzerie (Cerie), Zrnovsko (Zarosh), and Lesko (Lepis). This is where the scene is laid of “The Prespa Bells”, a novel written by Bulgarian author Dimitar Talev, a native of Prilep (modern Republic of Macedonia), which depicts the struggle of the Bulgarian population in Macedonia for liberation from Ottoman rule in the 19th and 20th centuries. The mythical town of Prespa portrayed in Talev’s work is fiction; existent in reality isonly Lake Prespa.

MALA PRESPA

Lake Prespa is situated in the territories of Albania, Greece, and Macedonia. At present, there are 9 villages in the Mala Prespa area inhabited by 5-7 thousand people some of whom have Bulgarian, and some – Macedonian consciousness. Ethnographer Vassil Kanchov cites Pouqueville mentioning that “in the early 19th century, Prespa was populated with Bulgarians alone. Arnaut migrations to Prespa began from the village of Trn or Tern, lying between theDevol River bed and Lake Mala Prespa, and then moved up further to the north”1. These villages are Eastern Orthodox and have both Bulgarian and Albanian names – Gorna Gorica (Gorica Madh), Dolna Gorica (Gorica Vogel), Tuminec (Kalamas), Glubočani (Golumboc), Šulin (Belas), Pustec (Likenas), Tzerie (Cerie), Zrnovsko (Zarosh), and Lesko (Lepis). This is where the scene is laid of “The Prespa Bells”, a novel written by Bulgarian author Dimitar Talev, a native of Prilep (modern Republic of Macedonia), which depicts the struggle of the Bulgarian population in Macedonia for liberation from Ottoman rule in the 19th and 20th centuries. The mythical town of Prespa portrayed in Talev’s work is fiction; existent in reality isonly Lake Prespa.

MALA PRESPA

Lake Prespa lies 30 km north of the town of Korçë, a distance travelled for about 45 minutes on a narrow road meandering up in the mountain. The village of Pustec is situated in the middle of Mala Prespa, on the Lake Prespa shore; it has around 300 houses and as many as 1200 inhabitants. On the mountain top, next to the traditional Albanian pillboxes, an Eastern Orthodox chapel has been erected.We entered the village on an October early afternoon2, along with a rickety bus arriving from Korçë, a vehicle which seemed to be about to fall apart any moment. Seen around were neat houses with dried red peppers and ropes of onions hanging on the walls. We walked past friendly-looking women in cotton-print skirts, wearing white or patterned head scarfs; the men were doing their daily jobs outside the houses, some were occupied with work by their boats. Local people catch dace in the lake. As we toured round the muddy village streets, we enquiredpeople what their origin was. We asked them in Bulgarian, they answered in their own dialect.“We are all Macedonians”, was the most common answer. “In 1920, when Greece came over, it was Greek rule here and we studied Greek. When Ahmed Zogu came in 1924, we studied Albanian. In 1945 teachers came from Macedonia and we began having classes in Macedonian. We start learning Albanian from the 4th grade of the elementary school, until then we have lessons in the Macedonian language”, explained L. B., a 73-year-old man. We inquired whether life was better now than in the Enver Hohxa era. “Life is better now. You can go and work wherever you like”, responded the old man who was satisfied with his pensionof 7000 leks (around 50 euros).

1. Кънчов, В. Избрани произведения. Т. 2, Наука и изкуство, София, 1970, с. 385.

2. Fieldwork in Albania, 25-31 October 2003: A. Zhelyazkova, A. Chaushi, V. Grigorov, D. Dimitrova, T. Mangalakova.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 3

An aged woman told us about her difficult life. “We keep working, but the land isn’t good here. Many of our people work in Greece and in Macedonia. All of us have Macedonian passports; it’s easier for us to gad about Macedonia. Why go to Bulgaria, when we’ve got no money”, said theold woman who had a pension of 20000 old leks (2000 new leks, the equivalent of about 15 euros). “How do you live on that little money, I say, sister?” she complained. M. M. (a 45-year-old female) told the team that all village dwellers had Macedonian passports. She and her husband had travelled to Skopje and submitted an application for Macedoniancitizenship; they had paid DM 100 and a month later they were Macedonian citizens. There is no employment available in the village. Using their Macedonian passports, Pustec people leave the place to earn their living in Macedonia. When asked what kind of jobs they found there, since in Macedonia itself unemployment was quite high, their reply was short: “As day-labourers”. For a week-long work there, they receive 10-20 euros. Other people travel to Korçë or Greece to earntheir livelihood - cutting wood, or working in construction for a small pay. The construction of a church of St. Michael the Archangel had been started in the centre ofPustec. At the time we visited the place, the construction was “frozen”, because there were nofunds. The villagers would not accept assistance from the Greek Church; they believe they belong to the Macedonian Orthodox Church3. Under Enver Hoxha, the local church building wastransformed into a shop. There was a school where classes until the 4th grade were in Macedonian. In Pustec, Radio Prespa has begun broadcasting in Macedonian since 2002. Newsand music have been on the air in four neighbouring villages. This radio station is owned by thePrespa Association, the Pustec-based organisation engaged in protecting the rights of ethnicMacedonians in Albania, and the equipment has been donated by the Council of Radio Broadcasting of the Republic of Macedonia. D. is a seventh-grade student. He studies Albanian, English, and Macedonian. He said there werestudents from the village at the Bulgarian universities in Sofia and Veliko Tarnovo. “When I finish school, I’ll go to Korçë and then to Bulgaria or Skopje to get a university degree”, was how he summarised his plans for the future. With support from Canada, three years earlier the Church of St. Athanasius had been built, while the new church was being erected with funding from the Republic of Macedonia, explained teacher S. The local people depend for their livelihood on raising sheep, goats, cows, and on growing wheat and maize. On the outskirts of the village, on the lake shore, a Christian cross isvisible – as evidence that “the old village had lain there and there had been a church”. According to S., the island in Lake Prespa is named Male grad, standing there is a church which King Samuel attended in his day; there had been a burial ground too. Pieces of ceramics from the Bronze Age have been found there. Twenty-year-old A., who studies law at the University of Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, explainedhow in the local elections held in the autumn of 2003 they had re-elected their old mayor, a Socialist, because he had promised to repair the road leading to the village, as well as the village streets. In the Prespa region everybody knows everybody; the young people are married at 21-22 years of age. “In Prespa, you’re already an old bachelor at the age of 25-26. People begin to gossip about you, for there must be something wrong with you if you haven’t got married by that age”, said A. His parents work in Lerin, Greece. One of those living in Pustec is uncle S. who is the head of the Mala Prespa section of the Ivan Vazov Bulgarian association. He organises Sunday schools in Bulgarian held on Saturdays and Sundays, two hours per week, in the nearby town of Pogradec and in Prenjas. Bulgarian is not 3The Macedonian Orthodox Church has not been recognized as autocephalous. – Author’s note.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 4

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 3

An aged woman told us about her difficult life. “We keep working, but the land isn’t good here. Many of our people work in Greece and in Macedonia. All of us have Macedonian passports; it’s easier for us to gad about Macedonia. Why go to Bulgaria, when we’ve got no money”, said theold woman who had a pension of 20000 old leks (2000 new leks, the equivalent of about 15 euros). “How do you live on that little money, I say, sister?” she complained. M. M. (a 45-year-old female) told the team that all village dwellers had Macedonian passports. She and her husband had travelled to Skopje and submitted an application for Macedoniancitizenship; they had paid DM 100 and a month later they were Macedonian citizens. There is no employment available in the village. Using their Macedonian passports, Pustec people leave the place to earn their living in Macedonia. When asked what kind of jobs they found there, since in Macedonia itself unemployment was quite high, their reply was short: “As day-labourers”. For a week-long work there, they receive 10-20 euros. Other people travel to Korçë or Greece to earntheir livelihood - cutting wood, or working in construction for a small pay. The construction of a church of St. Michael the Archangel had been started in the centre ofPustec. At the time we visited the place, the construction was “frozen”, because there were nofunds. The villagers would not accept assistance from the Greek Church; they believe they belong to the Macedonian Orthodox Church3. Under Enver Hoxha, the local church building wastransformed into a shop. There was a school where classes until the 4th grade were in Macedonian. In Pustec, Radio Prespa has begun broadcasting in Macedonian since 2002. Newsand music have been on the air in four neighbouring villages. This radio station is owned by thePrespa Association, the Pustec-based organisation engaged in protecting the rights of ethnicMacedonians in Albania, and the equipment has been donated by the Council of Radio Broadcasting of the Republic of Macedonia. D. is a seventh-grade student. He studies Albanian, English, and Macedonian. He said there werestudents from the village at the Bulgarian universities in Sofia and Veliko Tarnovo. “When I finish school, I’ll go to Korçë and then to Bulgaria or Skopje to get a university degree”, was how he summarised his plans for the future. With support from Canada, three years earlier the Church of St. Athanasius had been built, while the new church was being erected with funding from the Republic of Macedonia, explained teacher S. The local people depend for their livelihood on raising sheep, goats, cows, and on growing wheat and maize. On the outskirts of the village, on the lake shore, a Christian cross isvisible – as evidence that “the old village had lain there and there had been a church”. According to S., the island in Lake Prespa is named Male grad, standing there is a church which King Samuel attended in his day; there had been a burial ground too. Pieces of ceramics from the Bronze Age have been found there. Twenty-year-old A., who studies law at the University of Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, explainedhow in the local elections held in the autumn of 2003 they had re-elected their old mayor, a Socialist, because he had promised to repair the road leading to the village, as well as the village streets. In the Prespa region everybody knows everybody; the young people are married at 21-22 years of age. “In Prespa, you’re already an old bachelor at the age of 25-26. People begin to gossip about you, for there must be something wrong with you if you haven’t got married by that age”, said A. His parents work in Lerin, Greece. One of those living in Pustec is uncle S. who is the head of the Mala Prespa section of the Ivan Vazov Bulgarian association. He organises Sunday schools in Bulgarian held on Saturdays and Sundays, two hours per week, in the nearby town of Pogradec and in Prenjas. Bulgarian is not 3The Macedonian Orthodox Church has not been recognized as autocephalous. – Author’s note.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 4

taught in the Albanian public schools, but only in some private language schools in three Albanian towns – Tiranë, Elbasan, and Korçë. We asked him what the people in Prespa were –Bulgarians, or Macedonians. “Some believe themselves to be Macedonians, some believe they’re Bulgarians”, uncle S. answered.

“105 villages are willing to study the language. Courses are being organised”. He continued with his account how on three occasions the authorities hadsummoned him to inquire why he was organising Bulgarian language courses. “The Mala Prespasection works to prevent us from forgetting our tongue, our letters, our culture. We have a folklore group, we have kept our costumes, We maintain contacts with Bulgaria”, he recounted. In his opinion, all the villages around Lake Prespa have Bulgarian place names, and the local people speak a Bulgarian dialect. “The Pustec village was earlier called Ribartzi; it was near the river and people caught fish. Then, the second name became Rekartzi, because of its vicinity withthe river [reka]. And so it is, little by little, the Ignatia road goes right to Manastir and the Lerin parts and Salonika; here, by the riverside, the town even grew into two quarters: Mali grad –Mali Pazar, Golem grad – Golem Pazar, that’s how the place near Tumbinec was called. But today it’s Tumbinec. Its name used to be Golem Pazar. Well, they even built a large hotel near Mali grad and King Samuel, his daughter named the hotel “Prespina”. So, this large lodging place [prespalishte] got its name Prespina from the Bulgarian language”

4.According to uncle S., many places in Albania have Bulgarian toponymy. He enumerated the names of the villages lying beyond Moravia, with their Albanian and Bulgarian designations – Vrbnik, Bilishta (Biglishta), Znblak (Sonblak), Hocishte, Poloska (Ploska), Kapshtica (Krapešnica). Within the Korçë area are Borja, Drenovo, Dvorani; in Moravia – Podgorje, Alarup (“This one is made up of two words “God’s urop”. “Urop” means God’s little hammer. Fine ore was found here, that’s why they called it Alarup – Allah – of God”, explained uncle S.), Charava (Chernava), Pretusha, Gribec, Girk, Mochani, Malik, Krushova, Vinchani (“A lot of grapes were grown here”, uncle S. said), Voskop, Gergevica, Moskopoje (Moskopoli), Vitkuchi (Viskok “visokii skok” [high jump], the respondent specified), Lubonja, Pepalash, Nikolicha (Nikolica), Shtika, Vodica, Luarasi, Gostilisht, Erseka, Borova, Barmash, Kovachica, Radini, Petrini, Furka,Charshova, Leskovik. “Then it’s Berat – Beli grad, and Durrës – Dobrinija, and so on. The toponyms have all been changed”, uncle S. went through them name by name. People in Prespa are not familiar with history We visited 30-year-old B., born in Pustec, but living in Korçë, and became acquainted with her family’s history. B.’s mother was born in Pustec, and her father is an Eastern Orthodox Albanian. They had moved to town when B. was 4 years old. B.’s grandmother, aged 78, recalled that in her day there was not any Macedonian school. “When I came to Korçë, I couldn’t even buy myself bread, I didn’t speak Albanian. I learnt it from my friends”, she droned on in an old-time Bulgarian dialect. We wanted to know why most of the people in Mala Prespa thought themselves Macedonians.“I’ve learnt Macedonian from my grandmother in whose house only Macedonian was spoken. It was difficult for me when I arrived in Sofia to study law. I lived 10 years in Bulgaria, I came to know history and I’m aware I’m Bulgarian and the people in Prespa are Bulgarian too. But they’re not to blame for not knowing history. Besides, Bulgaria has done nothing for these 4Uncle S.’s account is given unedited. – Author’s note.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 5

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 5

55

people. Whereas Macedonia is concerned about them, gives them textbooks, it’s natural for these people to have Macedonian rather than Bulgarian consciousness. All Macedonians in Macedonia know about Prespa and say: “You’re our folk”, while in Bulgaria they don’t know much about Bulgarians in Prespa”, explained B. B.’s family visits Pustec only in summer, during holidays. None of those who have moved to the towns want to sell their houses in the village. Prespa’s population earn just enough to keep body and soul together, there are no jobs; the younger people go away to work in Korçë and theysupport the older ones. In spite of migration from rural to urban areas, the Mala Prespa region is not as depopulated as the mountain villages in Bulgaria, where only elderly people have remained. Many children are seen pottering about in the narrow, mud-covered streets of the hamlets of Mala Prespa. Vrbnik Settlers in Korçë Some of the residents in the town of Korçë are migrants from the village of Vrbnik, situated on the Albanian-Greek border. There is a four-grade school in Vrbnik, where lessons are in Macedonian. One of the Vrbnik settlers is D. B., a 37-year-old professor in Albanian, Balkan languages and culture at the University of Korçë. He has graduated from the Southwestern University of Blagoevgrad with a degree in Bulgarian philology. “At present, there are only 2 or 3 Bulgarian families in the villages of Boboshtica and Drenovjane (Drenova in Albanian), theothers have either been assimilated or have moved to Tiranë and Korçë. Those who are familiar with the specific local dialect know it’s very close to the standard Bulgarian language. My village, Vrbnik, lies by the border with Greece, in the Kostur region, known from Vassil Kanchov’s travel notes. Only the old people have remained to live there, the young ones have been migrating either to Greece or to Albania’s towns; only those occupied with cattle-raisinghave remained, because it’s a mountain village”, recounted D. B. The fieldworkers asked him what the difference between the dialect spoken in Vrbnik and that spoken in the villages around Lake Prespa was. “The Old Bulgarian nasal sounds (nasals) have been preserved in the dialect of the village of Vrbnik, it differs phonetically from the dialect spoken in the Lake Prespa area, which’s close to the Vardar dialect”, specified D. B. What is this language – Bulgarian orMacedonian? “It’s Bulgarian! To me as a philologist, there’s no Macedonian language”, was his answer. In his opinion, only people who want to study at universities in Bulgaria show interest inthe Bulgarian language. In the courtyard of the University of Korçë, we made acquaintance with E.M., a student ineconomics, born in the village of Dolna Gorica, and we talked about the population in Mala Prespa. In his view, its inhabitants are about 5000, “nine purely Eastern Orthodox Macedonian villages”. In the village of Dolna Gorica, consisting of about 80 houses and 300 dwellers, “all Orthodox Christian”, children go to elementary school where the medium of instruction is Macedonian. Twenty families have emigrated to Greece; others have migrated to some of the Albanian towns. “Our elderly people speak in Macedonian. We are entitled to instruction in Macedonian until the fourth grade of the primary school and later, optionally, from the 4th to the 8th grades – for as much as 60 per cent of the matter studied we have the right to classes inMacedonian, as well as for some particular subjects.” E. M. had finished high school in the town of Bitola, the Republic of Macedonia. The teammembers were interested whether people from his village travel frequently to Macedonia. “We all have Macedonian passports, we don’t need visas. I got my passport in 1998, but most of the people did in 2000.” We asked E. whether he knew if there were ethnic Bulgarians in Mala

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 6

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 6

Prespa. “I haven’t heard of any Bulgarian population in Albania.” According to him, there were ethnic Macedonians in Golo Brdo. “In Debar, in the village of Vrbnik and in the towns of Kukës, and Tiranë, there are Macedonians. The overall number of Macedonians in Albania is 100 000”, he said. “I don’t have any hopes for the future. I mean to emigrate. Things in Albania aren’t going to change for the better soon”, was how E. described his plans for the future. My first meeting with a Mala Prespa local was in February 1998. In a Tiranë street, I asked a young man, aged 30 or so, to show me the way to the Bulgarian embassy. He suggested that he should accompany me, since he was going the same way. When I learnt he was a native of the Mala Prespa region, I asked him to talk in his mother tongue. The man said he was a teacher andshowed me a book he had written and published in Albanian. He himself was surprised we understood each other without an interpreter. “Until now I thought I spoke in Macedonian, but now I see this language is also Bulgarian”, that is what the teacher from Prespa found out, all byhimself, at the conclusion of our conversation. GOLO BRDO Golo Brdo is a mountain region in north-eastern Albania, part of the Bulciza and Librazhd provinces. It borders on the Republic of Macedonia. According to data from the 2001 census, the number of the population in its municipalities is 8200, including 1800 families. The local people are Muslims. The men are known for their building skills, the best builders in the whole of Albania, and traditionally work for a living abroad. The roads in Golo Brdo are in poor condition,there is no sewerage, no telephones, no jobs; the region is economically underdeveloped. In October 2003, Boris Zvarko, an engineer from the village of Stebljevo, drafted a project worth 200 000 dollars for the installation of telephones in Golo Brdo. Administratively, Golo Brdo includes three municipalities comprising 26 villages: Trebista(Trebisht in Albanian), Ostrene, and Steblevo. The municipality of Trebishta consists of the following villages: Trebishta (Muchin) – the administrative centre with 135 families, 600 inhabitants; the village of Trebishta (Balja) with 100 families, 470 inhabitants; the village of Trebishta (Chelebie) with 140 families, 650 inhabitants; the village of Klenje with 30 families, 120 inhabitants; the village of Ginovetz with 3 families, 10inhabitants; the village of Ostren (Ostrene) and the village of Vrnica with 4 families and 15inhabitants. The Ostrene municipality includes the following villages: the administrative centre is the villageof Golemo Ostrene (Ostrene i Madh) with 300 families, 1200 dwellers; Lešničane (Lechan) with 20 families, 90 dwellers; Orzanovo with 20 families, 80 dwellers; Golemi Okštun with 65 families, 300 dwellers; Oresnie with 20 families, 100 dwellers; Malo Ostren (Ostren i Vog) with100 families, 540 dwellers; Tuček with 190 families, 540 dwellers; Ladomirica (Ladomirice)with 190 families, 540 dwellers; Pasinke with 190 families, 540 dwellers; Trbače with 190 families, 540 dwellers. The municipality of Stebljevo includes the following villages: Stebljevo, as administrative centre – 35 families, 120 dwellers; Zabzun with 100 families, 470 dwellers; Borovo (Borovë) with 100 families, 550 dwellers; Lange with 30 families, 120 dwellers; Sebište with 15 families, 150 dwellers; Moglica with 4 families, 15 dwellers; Prodan with 20 families, 80 dwellers.Bulgarian is spoken in 23 villages, 17 of them are purely Bulgarian, and the rest are mixed, according to H. P., head of the Prosperitet Golo Brdo Association. The ethnic Bulgarian villages

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 7

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 7

in Golo Brdo have both Albanian and Bulgarian place-names – Steblena (Stebljevo) , Klenja (Klenje), Trebisht (Trebišta), Ostreni i Madh (Golemo Ostrene), Ostreni i Vogel (MalkoOstrene), Gjinavec (Ginovec), Tucepe, (Tucep), Sebisht (Sebišta), Borove (Borovo), Zabzun (Zabzun). The population in the last two villages includes Bulgarians and Albanians. The Prosperitet Golo Brdo Association is concerned with the preservation of the traditions, folklore and customs of the Bulgarian population; it organises Bulgarian language courses. Its activities are basically focused on establishing cultural and economic contacts and relations with Bulgaria; among its objectives is also the opening of a Bulgarian college in Tiranë. S. H. P. is a native of the village of Stebljevo and we talked without an interpreter. He told usabout their collaboration with Bulgaria dating from 1992. In the preceding period, for years on end they had had no information and contacts whatsoever. On the beach at Durrës, four womenfrom Stebljevo, residents of Elbasan, met some women from Bulgaria. They found out they spoke the same language. After the Bulgarian women returned to Bulgaria, VMRO representatives – Spas Stashev, Krassimir Karakachanov and Evegeni Ekov, visited Golo Brdo. An association named Stroitelite ot Golo Brdo [The Builders of Golo Brdo] was registered, and, later, another one – Prosperitet – Golo Brdo. “I’ve been to the court four or five times in order to register the association”, reported H. P. The Bulgarian language in Golo Brdo has been preserved, although the people do not know Bulgaria. “We speak Bulgarian at home, we sing and dance; it’s from our infancy that we’ve begun speaking Bulgarian.” In no single school in Golo Brdo is the Bulgarian language taught. Before going to school, most of the children already speak the language which they learn at home, and only after the age of 6 do they begin to speak Albanian. In the village of Vrnica, there were Bulgarian teachers in 1912-1914, H. P. said. “In this place, the Serbs [are said to have] had many problems with the Bulgarians. The Bulgarians had a frontier between Stebljevo and Klenje. Our village had been driven away from Serbia three times.We say “madjiri” (migrants), “muhacir” in Turkish. All were Christians, and there are manypeople that have two names. For example, Gjon and Kostadin have also Muslim names.” H. P. elaborated on what awareness the people in Golo Brdo had of their identity. “At first, wedidn’t know who we were, what our origin was. We were self-aware, but we didn’t knowBulgaria. We started the association with 168 people, all intellectuals. We want contacts with Bulgaria not for the sake of assistance alone, but in order to have her come here and be involved with some economic projects. Bulgaria could never become related with us unless this is done.” In addition to ethnic Bulgarians, in Golo Brdo there are people who have Albanian consciousness, as well as such of Macedonian identification. “Those ones, the Macedonians, are more powerful, more aggressive; Macedonia itself works more aggressively among us… Bulgaria has a different state conception. It’s better for us to work with Bulgaria, in a more normal, more composed, more peaceful way, free of any complexes. We don’t have here in Golo Brdo many of the things Albanian, we don’t have blood feuds, nor Kanun.” The men in Golo Brdo travel abroad to Greece, Italy, and Germany to earn their living. Currently,the population keeps migrating to the large towns – Tiranë, Durrës. Now, only 20 out of 200 houses are populated. “From Stebljevo alone there must be some 720 households in Tiranë”, said H. P.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 8

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 8

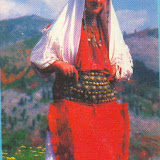

A Steblevo-born Bulgarian woman’s account A. C. was born in the village of Stebljevo where she lived until the age of 2 and a half years. “People in Stebljevo speak a dialect they haven’t studied at school. We don’t sing in Albanian at our wedding celebrations, but in Bulgarian”, explained A. C. who had graduated from theFaculty of Law at St. Kliment Ohridski University of Sofia, Bulgaria, and currently worked at astate institution in Tiranë. She lives in the Kodra e Priftit neighbourhood of Albania’s capital, 20 minutes from the city’s centre, together with many other migrants from Golo Brdo – from the villages of Stebljevo and Trebishta. “The people in our neighbourhood speak their own dialect; the children speak Bulgarian [too].In my uncle’s family, they speak only Bulgarian, and in our family we speak Albanian. My grandmother, who doesn’t speak Albanian well, was eager to listen to the Bulgarian language; when I used to come back from Bulgaria on vacations and when I read her some book, she said she didn’t understand anything. But she could understand the words of the Bulgarian songs”, recounted A. C. In her opinion, Golo-Brdans assume they speak a dialect, but do not know what it is. “Mygrandmother told me we spoke “in Bugarski”, she never mentioned our dialect as beingMacedonian. When Macedonians come to Golo Brdo, they say people speak Macedonian; whenBulgarians come over, they say this dialect is Bulgarian”, she specified. “My idiom is closer to the Prespan one, rather than to the standard Bulgarian language”, concluded A. C., who traveled to the Mala Prespa region together with the team. During her university studies in Bulgaria she mixed with Albanians exclusively. She mentioned as a reason for this the fact thatshe was older than her fellow-students. Besides, she believed Bulgarians were prejudiced against Albanians. A. C. told us about the festivities of Golo-Brdans – they sing, play zurnas, beat drums, and dance horos. Until 6-7 years earlier, they used to intermarry in Golo Brdo. A. C.’s mother and father are fifth-generation cousins. The female wedding costume consists of a pleated white blouse, belt buckles, a red sleeveless jacket, a red shamliya (head scarf) with silver threads, and many-coloured woolen socks. The male costume includes a white cap, a yellow belt, a long, pleated, white shirt, a sleeveless jacket, and a red coat worn over it. When a bride comes to the house, she dips her finger into honey and butter and smears the door with a light touch. The bride and the bridegroom are given pieces of the wedding round loaf. On Sunday, they shut the bride and the bridegroom in a room. The bridegroom is ritually beaten with a piece of wood, as if he was reluctant to stay closed in with the bride. The wedding-guests sing by the door. On Saturday afternoon, they take out the drums and the wedding banner. On the tip of the banner pole there is an apple and it is decorated with flowers and the boy’s cloth. It is considered a great honour to carry the banner and the latter is conferred to the groom’s closest friend. Tuesday begins with the preparation of a round loaf at the bridegroom’s place, while the women go to inspect the dowry. The dowry items are washed before the festive day; Thursday is the day the dowry is taken in. The region’s culinary specialty is komat, a dish prepared of nettle – “they dry the nettles, boil them, add curds, leave them to ripe, and cover them with sheets of pastry”. When a child is born,they make baklava and maznik, with sheets of pastry, adding only butter and sugar. THE POLICIES OF TIRANË, SOFIA, AND SKOPJE Albania has a population of 3 087 000, according to the 2001 census data. The ethnic composition of the population is as follows: Albanians – 95 per cent, Greeks – 3 per cent, and

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 9

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 9

others – 2 per cent (Wallachians, Roma, Serbs, Montenegrins, Macedonians, Bulgarians). These figures are questionable, since in the April 2001 population census questionnaire forms there were no entries for religion, language, and national identity. On 25 November 2003, during an international scholarly conference held under the auspices of the German Embassy in Tiranë, an Albanian geographic and demographic atlas was presented.This encylopaedic work has been the result of the co-operation among the University of Tiranë, the Centre for Geographical Research at the Academy of Sciences, the University of Pristina, the University of Potsdam and the Higher School of Technical Sciences in Karlsruhe. The Atlas provoked a debate among the Albanian intelligentsia whether the Aroumanians in Albania are a cultural or an ethnic minority. “The conclusion of this atlas is surprising, to say the least, because for the first time ethnic minorities have exceeded 10 per cent – the official figure is 2-3 per cent, in particular zones predominantly, like the one in Gjirokastër. What’s more, in contrast to past practice, some cultural groups such as the Aroumanians, the Roma etc. have been defined in theAtlas as ethnic minorities … When the matter in hand concerns minorities in Albania, surprises never end – the Macedonians in 9 villages near Prespa realised they had run up to over 500 000,the Roma concluded they were at least 300 000, the representatives of the organisations of theGreek minority didn’t present any figures. In this Albania, with a population of 3 million, theAlbanians have remained the only minority not claiming large numbers, perhaps because if all minority claims were taken into account, there would be no place for them left in this country”, writes the Albanian “Klan” magazine 5. Tiranë shows concern about the protection of the national rights of Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia, but in Albania itself there are no accurate data on the number of minorities. In 2001, when the population census in Albania was taken without recording religious and ethnic identification, many politicians and administrators in Albania raised their voices in favour ofincluding forms in Albanian in the census to be taken in the Republic of Macedonia. In aconversation with R. L., chief of a non-governmental organisation based in Tiranë, the teammembers expressed their opinion that the situation is rather paradoxical. “You are quite right when saying there should be minority statistics in the census. I’d like to see religion… I think that Muslims are not 65 per cent and, in my opinion, the census should clarify this question. To identify, for example, if I am a Muslim and my wife an Orthodox Christian, and what my daughter is, etc. In my view, the most important characteristic in the census is the religious and not the ethnic one”, he remarked. Albania admits the presence of minorities by bilateral international agreements. However, there is no agreement between Tiranë and Sofia settling the issue of the Bulgarian minority. Tiranë acknowledges there is a Macedonian minority in Mala Prespa entitled to instruction in their native tongue until the fourth grade. “In my opinion, the population in Golo Brdo is also a minority, but you yourselves should say whether they are Bulgarians, or Macedonians. They themselves don’t know whether they’re Bulgarians or Macedonians. The way there’s no problemwith recognising Montenegrins as a minority, there will be no problem at all to acknowledge a Bulgarian minority. We aren’t neighbours, and we have no problems with the borders. During the communist era they simply didn’t know they were a minority, and, after all, everybody calls himself as he likes, they identify themselves as Macedonians, so we accept them as such. If it turns out they are Bulgarians, we’ll accept them as Bulgarians”, R. L. said.

5. Shameti, S. Quelle place pour les Aroumains d’Albanie? Klan, Décembre 2003, Le Courrier des Balkans,http://www.balkans.eu.org/article3938.html.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 10

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 10

The joke about the Bulgarian and the Macedonian ambassadors In Albania, it is only non-governmental organisations that study minorities. In 1999-2000 the Albanian Helsinki Watch Committee (AHC) carried out two surveys in the region of Mala Prespa, where, according to its report, the population is a Macedonian minority. “The minority we describe as a Macedonian one, lives in the areas around Prespa and Korçë and numbers 5-7 thousand people inhabiting the territory of 9 villages. The region is prospering, and these people are allowed to maintain contacts with Macedonia, from which they largely benefit. There areprimary schools in the 9 villages inhabited by a Macedonian minority; in two communities there are high schools where Macedonian is taught. All the schools have established contacts with schools in Macedonia. The students continue their studies at universities in Tiranë, Skopje, and Bitola. Members of this minority travel to Macedonia for medical treatment which is free. In Pustec a church has been built. The minority population in Prespa can travel visa-free to Macedonia paying only a monthly fee”, said A. P., expert in international law, member of AHC Managing Board6. Prof. A. P. commented on the thesis maintained by the Bulgarian historians that the minorityliving in the Prespa area is Bulgarian, offering a standard answer commonly given by many Albanian observers and politicians on the subject of ethnic Bulgarians in Albania. “We call thisminority Macedonian, and I believe there is a very strong affinity between Bulgarians and Macedonians. You are to decide what it is. To us this population is a minority with its own characteristics”7. In conversations with politicians from Albania on the subject of a Bulgarian minority, several respondents related the same episode – about how the Bulgarian and the Macedonian ambassadors visited Golo Brdo and Mala Prespa, and the local people would change their identification as the occasion required. These respondents suggested, by way of a joke, that we – Bulgarians and Macedonians – should get to terms over the issue of what the national identity of the population in these regions was. “It’s difficult for us to differentiate between Macedonians and Bulgarians in Albania. Around Prespa Lake there is a community of very nice people and our party has followers there. I’d like to make a joke by saying that when the Macedonian ambassador to Tiranë makes visits to those quarters, they tell him they are Macedonians, and when the next week the Bulgarian ambassador visits them, they say they are Bulgarians. Now we come to the question of the identity of Slavo-Macedonians, of the Pirin Mountain – is it Macedonian or Bulgarian. There’s history and there’re dialects, and it’s not for Albania to settle this issue”, remarked G. P., party leader in Tiranë, in the summer of 2001. “If they are Bulgarians in Golo Brdo, what on earth is the Macedonian ambassador doing there?” wondered R. L. Official representatives in Tiranë also mentioned the story of some envoys from Sofia and Skopje both claiming that the minority is “theirs”. Is Albania ready to grant more rights to the Bulgarian population living around Lake Prespa and in Golo Brdo? In 1998, Pascal Milo, the then foreign minister of Albania, gave the following answer: “Two years ago, during the Congress of theSocialist International held in New York, a friend of mine – Secretary of the BSDP, asked me thisquestion. In ten minutes, another friend of mine from the Republic of Macedonia posed the same question. My response was: You are to determine whether this minority in Albania belongs to Bulgaria or to Macedonia and then come back to me to discuss its rights. After World War II, we

6. Mangalakova, T. Prof. Arben Puto denies there is Bulgarian ethnic minority in Prespa. In: сп. Балканите, бр. 18, 2001, с. 5. 7Ibid.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 11

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 11

know this minority is Macedonian. I’d rather not elaborate on why we chose this way, but the Communist regime made this decision and it’s difficult for us now to change that and say this minority is Bulgarian, and not Macedonian. This is a serious dispute between Bulgaria and Macedonia. The Albanian government is ready to grant this minority the largest possible cultural autonomy, educational rights based on the international standards”8. The only Albanian politician, who straightforwardly admitted the presence of ethnic Bulgariansin Albania, was former Prime Minister Aleksander Meksi: “I wouldn’t like to offend anyone who would call himself a Macedonian, but in the territory near Lake Prespa there is a school instructing in Bulgarian”9.50 000 Bulgarians, or 350 000 Macedonians?The official Bulgarian policy pursued after 1989 has avoided making declarations on the status ofthe Bulgarian minority in Albania. Donation campaigns in favour of the Bulgarians in Golo Brdo, carried out under the patronage of the President, provided the occasion to speak out about this population. The Ministry of Education and Science and the State Agency for Bulgarians Abroadare the government institutions committed to the Bulgarian minority in Albania. During his visitto Tiranë in March 2003, Prime Minister Simeon Saxe-Coburg Gotha met with representatives of the Bulgarian non-governmental organisations active in Albania. Discussed during the meeting was the opening of a Bulgarian secondary school in Tiranë. Released on the official web site of the Bulgarian government has been information stating that “The “Ivan Vazov” and “Prosperitet Golo Brdo” associations are legitimate representatives of the Bulgarian community in Albania and the State Agency for Bulgarians Abroad maintains close contacts with them. They play an intermediary role in the selection of students applying for higher schools in this country, and issue documents certifying Bulgarian origin… At present, the Bulgarian community in Albania numbers about 50 000 persons. They inhabit the areas of Golo Brdo, Mala Prespa, the villages of Drenovo, Boboshica and Vrbnik, as well as the municipality of Korçë.”10For the present, this isthe only official position Sofia has declared on the subject of ethnic Bulgarians in Albania. In 1993-2003, over 200 Albanian young people of Bulgarian origin studied at universities in Bulgaria. Greatest was the number of students from Golo Brdo, followed by those from the region of Gora and Mala Prespa. Education in Bulgaria is free, Bulgarian diplomas arerecognised in Albania. After returning to Albania, these graduates come to work successfully as teachers, university lecturers, journalists, servants in the public administration, or employees in the banking and business sectors. Many Bulgarian respondents in Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo insisted that Bulgaria should enforce a visa-free regime for ethnic Bulgarians in Albania or alleviate the procedure for getting Bulgarian visas and Bulgarian passports. This issue was discussed at a round table organised by the State Agency for Bulgarians Abroad (SABA) on 18 March 2003. Representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that making Bulgarian passports and visas available is a complex problem because of Bulgaria’s commitment as a state responsible for the Schengen area border control. Representatives from non-governmental organisations, from the Ministry of

8. Мангалакова, Т. Паскал Мило, министър на външните работи на Албания: Албанците трябва да участватпо-широко в управлението на Р. Македония. – In: Македония, бр. 22, 1998, с. 4.

9. Иванова, Т. Македонското правителство трябвало да даде повече права на албанците. Смята албанскиятпремиер Александър Мекси – В: Македония, бр. 47, 1993, с. 2.

10. Prime Minister Simeon Saxe-Coburg Gotha has received a letter of grateful acknowledgement from Bulgarian associations in Albania, http://government.bg/PressOffice/News/2003-10-03/7476.html.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 12

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 12

Education and Science, from SABA, and researchers ascertained that the Republic of Macedonia worked quite actively among the population of Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo, entitled to travelling visa-free to Macedonia, and that for the last several years the Macedonian ambassador to Tiranëhad repeatedly toured Mala Prespa handing out Macedonian passports. As a result of the conservativeness and bureaucratic attitude of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ethnic Bulgariancommunities in the Balkans, including ethnic Bulgarians in Albania, are not supported by the Bulgarian state, was the opinion expressed by B. E., former ambassador to a Balkan country. Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia have different conceptions of both the ethnic identity and the number of the population of Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo. According to Skopje, this is a Macedonian population speaking Macedonian language, and the number of Macedonians inAlbania amounts to 350 000 people. According to Sofia, there are 50 000 ethnic Bulgarians in Albania. Although some Albanian politicians and administrators declare that there are ethnic Bulgarians in Albania, no agreement has been signed between Sofia and Tiranë stating the presence of such a minority. Minorities in Albania are recognised by intergovernmental bilateral agreements. For the present, only a paper released by the Ministry of Economy of Albania and related to the work of a round table under the Stability Pact, mentions that there is a Bulgarian minority in Albania. “The overall number of minorities in Albania accounts for about 2 per cent of the population. The principal minorities are those of Greek, Macedonian, Russian, Bulgarian,and Italian nationalities, and a very small number of other countries’ nationals”11. A Bulgarian diplomatic source commented on this fact as a “great achievement”.The most active Macedonian association in Albania is “Prespa”. According to its leader,Edmond Temelkov, the interest of the Macedonians in Albania requires that the Macedonianprime minister lobby with his Albanian counterpart for establishing a free-transborder movement zone and for providing identity cards for the Macedonians in this area. Macedonia observes the status of the population in Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo with particularattention. Skopje wants that Macedonians should have the right to form political parties in Albania, as well as that Albania should officially that the population in Golo Brdo is Macedonian. On 12 October 2003, during the local elections in Albania, one of the accents in thecommentaries published in the Macedonian mass media was that among the candidates of the 39 political parties there were Macedonians, mainly members of the Macedonian association“Prespa”, who, not being allowed to found their own party, ran in the elections as candidates of other parties12. Skopje draws a parallel between the rights of ethnic Albanians in Macedonia and the rights ofethnic Macedonians in Albania. “What Albanians in Macedonia have, and what Macedonians in Albania could get, is the objective of the existing four Macedonian associations in Albania which have recently founded a Union of Macedonians in Albania seeking to create an all-Macedonianparty intended to defend the interests of nearly 300 000 Macedonians in our western neigbour country. They have been discriminated in terms of adhering to the international agreement on minorities, report the Macedonian representatives in Albania.”13

Covering the meeting on 13 November 2002 between Albanian Prime Minister Fatos Nano and his Macedonian colleague, Branko Crvenkovski, the Macedonian media made commentaries that

11. Ministria e bashkepunimit ekonomik dhe tregtise Secretariati Shqiptar per Paktin e Stabilitetit, Tryeza Kombetare I – Democratia, 3.

12.Тодоровска, В. Локални избори во Албаниjа. Вести, Телевизия А 1 – Македония, http://www.a1.com.mk/vesti/vest.asp?VestID=2467.

13. Стоилова, М. Македонците во Албаниjа се стремат кон семакедонска партиjа. Вести,Телевизия А 1 -Македония, http://www.a1.com.mk/vesti/vest.asp?VestID=21842.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 13

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 13

in Albania only the Macedonians in Mala Prespa enjoy the status and rights of a minority. For many years, the Macedonians in Golo Brdo and Gora have insisted on being granted minoritystatus and rights, but they have not obtained them yet14. King Samuel For their lessons, the children attending Macedonian language schools use textbooks translated from Albanian. “In the history textbooks, King Samuel is described as a Bulgarian, somethingone can’t keep silent about”, was a commentary heard during a discussion held in Pustec on 7 April 2002 on the occasion of the 11th anniversary of the “Prespa” association15. The debate whether King Samuel was Bulgarian or Macedonian is parascholarly because historicaldocuments show there was no Macedonian state in those times. The identity crisis of the young Macedonian state has manifested itself, among other things, in Skopje’s attitude to the population in Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo. The young people from Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo who study at universities in Bulgaria or in Macedonia are not indifferent to the debate over history between Bulgaria and Macedonia.Samuel is a Bulgarian king for students in Bulgaria, while for students in Macedonia he is aMacedonian king. Albanians look with indifference, sometimes mockingly, upon the debate over Samuel’s identity. Extending relations with Bulgaria Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo are economically underdeveloped regions and for the past several years the population has migrated to Albania’s larger towns. Some of the younger people work abroad, mainly in neighbouring Macedonia and Greece. Bulgaria is yet to attract ethnic Bulgarians from Albania as a tourist destination and a place of residence, as a country ofemployment opportunities on account of the advantages it offers – no language barrier, goodeducation, chances to obtain Bulgarian citizenship. Since April 2004 Bulgaria has become anactual NATO member country, and in 2007 it is expected to join the EU. From now on, the contacts of ethnic Bulgarians in Albania with Bulgaria are to grow. The current tendency is for an ever increasing number of people in Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo to become aware of their Bulgarian origin, and the main factor in it are the students at Bulgarian universities. This will leadto closer cultural and economic relations with Bulgaria. A major role in this process could be played by non-governmental organisations in Bulgaria and in the Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo regions, but the level of contacts between them is still unsatisfactory. Ethnic Bulgarians inAlbania have lived in the course of long years in isolation, without maintaining any relations and contacts with Bulgaria and now they have to make up for lost time and missed opportunities. One of the unresolved problems is the lack of an alleviated procedure for obtaining Bulgarian visas by ethnic Bulgarians in Albania. For the present, the Bulgarian institutions do not planchanges in the regime. Over the last years the Republic of Macedonia has worked very actively among the population in

14. Средбата Нано – Црвенковски со посебен третман во албанските медиуми. Телевизия А1 – Македония, Вести, http://www.a1.com.mk/vesti/vest.asp?VestID=14832.

15. Македонците во Албаниjа до правата со протести. Вести, Телевизия А 1 – Македония, http://www.a1.com.mk/vesti/vest.asp?VestID=7615.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 14

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 14

Mala Prespa, chiefly in the sphere of cultural co-operation. As a result of the deepening crisis faced by the Macedonian state and its uncertain future, expectations are that the population of Mala Prespa will turn their eyes to Bulgaria. At the moment, many people in Mala Prespa haveMacedonian passports along with their Albanian ones, but the Bulgarian passports will becomemore attractive because with them one will be able to travel visa-free to the EU countries. After 2001, there has been an influx of Macedonians that have obtained Bulgarian passports attractedby the possibility for a legal 3-month stay in the EU during which they could work illegally there.An analogous rush for Bulgarian passports might be seen in the next few years among the population of Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo. A greater number of people in Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo are going to apply for Bulgarian citizenship. The procedure lasts for about a year. There are two points of view in Bulgarian society concerning the matter of Bulgarian passports for ethnicBulgarians living outside Bulgaria. VMRO (an opposition party describing itself as nationalist) has given the example of the Macedonian ambassador who toured Mala Prespa to hand out Macedonian passports. VMRO criticises the Bulgarian institutions on account of the cumbersomeprocedure by which ethnic Bulgarians apply for Bulgarian citizenship. The second view is more conservative and it is largely maintained by top Bulgarian officials – the procedure should not be revised because Bulgaria cannot receive large numbers of emigrants.Ethnic Bulgarians living outside Bulgaria who have no documents certifying their ethnic origin have to present a certificate of Bulgarian origin issued by the State Agency for BulgariansAbroad (SABA) and required in applying for Bulgarian citizenship. The papers are submitted tothe Ministry of Justice; some other state institutions, too, should make certain inquiries. “I cannot agree we should issue a certificate based on an [individual’s] signature alone, and a passportwith just two signatures. This is in contradiction to the elementary logic of the state’s commitments and our confidence that we are a normal administration... There is no collective procedure in resolving this problem, the approach is individual. I cannot agree that the approach of the Macedonian administration whose representatives are said to have been going about with suitcases full of passports and handing them out, is the better one. In terms of Bulgaria’s authority and positions lately, I can’t see anyone giving Macedonia as an example for us”, pointed out S. H, top SABA administrator. Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo are going to experience depopulation. Migration processes will leadto the obliteration of language and culture as major characteristics of population’s identity. It is possible that in one or two generations the Bulgarian language now spoken at home will be usedonly by the elderly people. The way of life, the customs and manners of the population in Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo should be studied and described by researchers and scholars. So far, none of the non-governmental organisations of the ethnic Bulgarians in Albania has its own web site. Because of the geographic isolation of these regions and the poor transport links andcommunications, one of the ways to increase contacts is to launch an internet portal or a web sitewhere various information will be published – for example, details about the application procedure for Bulgarian universities, different ways and channels for studying Bulgarian (even via Internet), etc. Increasing the contacts of ethnic Bulgarians in Albania with Bulgaria will lead to enriching Bulgarian culture and language in Bulgaria itself. However, this is a topic which is yet to be investigated.

Няма коментари:

Публикуване на коментар